Many websites which purport to give advice to exchange students will tell you that everyone should become an exchange student.

That’s nuts.

Definitely not for everyone

This is the correct formulation:

Everyone should probably think about becoming an exchange student.

But they should only become an exchange student once they’ve informed themselves about what exchange students do, and the pluses and minuses of becoming an exchange student, and made an informed decision based upon that information.

One of the aims of this website is to give you such information, to help you figure out whether or not a student exchange is something you’d like to do.

In order to figure that out, you need to consider two questions:

- What it is that exchange students actually do?

- Do you want to spend six months or a year or another period of time doing those things?

The aim of this page is to answer the first of those questions.

School

If you do decide to become an exchange student, you’ll spend the majority of your time attending school.

Of course, the school will be in another country, which will add novelty value and make it interesting, at first. After a while, though, your day-to-day routine will probably be very similar to the one you have (or had) as a school student in your home country.

The school that hosts you is unlikely to have high academic expectations of you. For example, unless you have arranged for the grades you earn whilst on exchange to count towards your grades at home, you probably won’t be required to sit exams or submit assignments along with the rest of the class.

However, the school (and your host family and exchange organisation) will expect you to show up to school, pay attention and take notes in class, and not disrupt your classmates. If you cut class regularly, your school and possibly your exchange organisation will ask you to improve your attendance, or leave.

If you don’t want to prolong your time in school, or can’t imagine yourself spending a whole year attending school rather than travelling or earning money or socialising, a student exchange is not for you.

Language learning

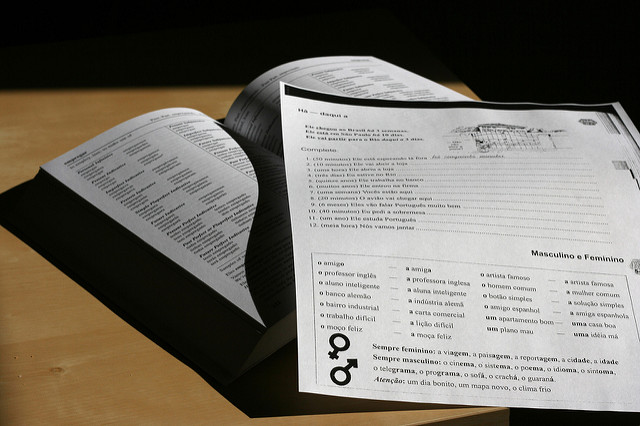

In addition to attending school, most exchange students have to spend a large amount of time learning a foreign language.

Learning a foreign language is far harder than most people imagine. True, you will learn much vocabulary and many idioms by osmosis because you are in a country where you are surrounded by people who speak the language. However, you will still need to spend many hours on your own rote learning vocabulary and grammar, and doing grammar exercises.

Your host family, school classmates and exchange organisation will take an interest in how your language skills are developing. To a degree, they will judge the success or otherwise of your youth exchange on how well you learn the language of your host country.

In other words, if you don’t learn their language well, they may think that your exchange has not been a good one. That may be an unfair assessment, but c’est la vie.

Don’t become an exchange student in a country where you’ll need to learn a foreign language if you aren’t prepared to work hard at learning that language.

Assimilation

One of the big aims of the student exchange movement is for exchange students to assimilate into the cultures of their respective host countries.

If you decide to go on exchange, your exchange organisation and host family will expect you to fit in with the routine and lifestyle of your host family. That means eating what they eat, keeping the same hours as them, respecting their belongings, adapting to their household rules and routines, respecting your host parents in the same way you respect your biological parents – if not more so – and making an effort to get along with your host siblings.

Outside the home, you will have to respect the laws of your host country, respect the rules of your school, and generally be a good citizen who keeps a low profile.

The flip side of all of this is that you will be expected to leave behind, or stop doing, some things that you do in your home country. Your parents at home might have no problem with you staying out until all hours, or staying up late on social media, or talking for hours on the phone, but your host family’s rules might not permit any of those activities. Likewise, you may participate in certain pastimes or hobbies at home that may be impractical for you to continue while you’re an exchange student. Fans of horse riding and playing the bagpipes, take note. You will have to find new pastimes in your host country to fill the void.

If you can’t imagine changing your lifestyle or habits, then a student exchange is definitely not for you.

Free time

Exchange students spend the majority of their evenings, weekends, and other free time with their host families.

Most host families will encourage exchange students in their care to socialise with people from their schools, other exchange students, and family friends. However, host families and exchange organisations also have a clear expectation that exchange students will spend a good deal of their free time at home with their host families rather than outside the home. They will certainly discourage students from treating the house of their host families as a hotel – as places for sleeping and getting free food in between socialising and partying.

If you want to spend a year or six months going out and meeting people and not spending any time at home in a family environment, a student exchange is not for you.

Travel

Being a foreign exchange student is not the same as being a tourist.

In fact, some exchange organisations or host families may prevent you from undertaking any independent travel. They may only permit you to travel in the company of your host family, or to visit people known by your host family, or as part of trips organised by your exchange organisation.

Note that, if you do become an exchange student, you will almost certainly have opportunities to travel. During my exchange year, I went on the following trips:

- A five-day skiing holiday with my first host family in the Swiss Alps.

- A weekend in Basel (city in Northern Switzerland), staying with another exchange student and her family.

- A five-day trip to Paris to visit my sister, who was also on exchange at the time.

- Another skiing holiday with my first host family.

- A two week long European tour organised by Rotary Switzerland.

- A weekend in French-speaking Switzerland with a family from my Rotary host club.

- A two-week visit to a small town in Bavaria, Germany, staying with Rotarians from the partner club of my Swiss host club.

- A weekend in Zermatt hiking in the hills surrounding the Matterhorn, with a couple from my Rotary host club.

- A week in Berlin with my third host family.

- A skiing holiday in the central Swiss alps with my final host family.

- Throughout the year, weekend trips to Geneva, Liechtenstein, Bern and other cities in Switzerland, organised by former Rotary exchange students, culminating in a final trip to Zermatt, where we snowboarded at the foot of the Matterhorn.

You get the idea. I did plenty of travelling. You will likely have similar opportunities, should you choose to go on exchange.

Note, however, that the travel will not be wholly on your terms and will rarely be unaccompanied. There almost certainly won’t be any month-long, solo backpacking trips around Europe. If you are interested in more independent travel, a student exchange is not for you. You would be far better off just taking a long holiday, or undertaking a university exchange later on.

Work

I’m not aware of any foreign exchange student who sought and obtained paid employment whilst on exchange.

For starters, the types of visas given to high school exchange students usually don’t allow the visa holder to seek paid employment. Even if you were able to get a working visa – which is surprisingly difficult in many countries – your exchange organisation may not allow you to work whilst you are on exchange.

If you want to work overseas, a student exchange is not the right way to do it. You need to consider undertaking a gap year or working holiday.

Drinking, driving, dating, drugs

If you decide to go on exchange, your student exchange organisation might prohibit you from drinking, dating, and certain other activities. The prohibited activities may include activities which you partake in at home, or which you feel you are entitled to partake in because of your age or because other people around you are doing them.

Rotary is mildly famous for prohibiting Rotary exchange students from drinking, driving, dating or taking drugs – the so-called “four ‘D’s”. No doubt other student exchange organisations have similar rules which they expect participating exchange students to abide by.

With the exception of the “no drugs” rule, most of these rules are a bit flexible. For example, nearly all exchange students get briefly romantically attached to someone while they’re on exchange. Such relationships are usually OK provided they don’t get too intense or too physical.

Exchange organisations and host families usually also tolerate a low level of drinking alcohol, particularly in countries like Belgium, Germany and France, where minimum ages for alcohol consumption are either low or routinely ignored.

Most exchange students will also operate a vehicle at least once or twice while they are on exchange, usually in the course of helping out their host families.

In a nutshell:

- Going to the movies or hanging out at school with a girlfriend while you’re on exchange is usually OK. Doing things that could result in her getting pregnant is definitely not OK.

- Having a beer at home with your host brother whilst watching a soccer game on TV is OK. Getting drunk and passing out in the city and missing the last train home is not OK.

- Reversing your host parents’ car out of the driveway so that your host father can get the other car out of the garage and park it on the street is usually OK. Cruising around town in your host parents’ car without them being in it is definitely not OK.

Of course, where the rules are not flexible is where the conduct in question is illegal in your host country. For example, the drinking age in most of the United States is 21 years old – beyond the age at which you can be a high-school exchange student. Exchange organisations usually also have a zero-tolerance policy for unlicensed and uninsured driving, sex with minors or non-consensual sex, drug trafficking, and drug consumption where it is illegal. Any such conduct will lead to the student being sent home at best, or reported to the police at worst.

If you want to spend your time drinking and getting high, getting intimate with other people and driving around, a student exchange is not for you. A university exchange in a few years’ time will give you more freedom to do such things.

Not just negatives

You may conclude from the paragraphs above that there are only negative things about being a foreign exchange student.

I hasten to add that there are many benefits to going on exchange, as well. From my perspective, the benefits far outweigh the limitations on freedom and other negative aspects outlined above. I am merely trying to give you an accurate picture of what being an exchange student is like, so that your decision about whether to undertake an exchange is an informed one. The issues outlined above seem to be the ones which cause exchange students (and their host families) the greatest trouble.

Typical foreign exchange student routine

So, what does a typical day in the life of an exchange student look like? Mine used to look something like this:

School day routine

6.00AM: Wake up, shower and dress for school, eat breakfast.

6.45AM: Leave home on bike for 10-minute ride to train station.

7.00AM: Board train for 45-minute train journey into town. Most other school students on the train spent the time studying. I spent the time cramming German grammar or trying to read German books (impossible and very slow at first, easier and easier as the year went on).

7.45AM: Arrive at train station closest to school. Walk to bus stop and board bus for 10-minute ride to school.

8.35AM: First lesson of the day started.

11.35AM: 90-minute lunch break started (note that many schools in Europe have a long lunch break to allow students to travel home and eat lunch with their parents).

1.05PM: Afternoon lessons began.

4.35PM: End of school day. Board bus for trip to train station.

5.00PM: Train home. Again, most students would spend the train trip studying, in order to get a head start on their homework.

6.00PM: Arrive home. Do homework, study German or read newspaper until dinner time.

6.30PM: Usual dinner time.

7.30PM: Social time with host family, usually spent watching TV, lingering over dinner and chatting, or (in summer time) doing something outside like playing table tennis.

9.00PM: Say good night to host family, brush teeth, prepare for bed.

9.30PM: Lights out.

Weekend routine

Friday night: After dinner, visit pub or café with host sibling or other exchange students.

Saturday morning: Sleep in (a necessity after five 6 AM wakeups in a row).

Saturday afternoon: Family lunch, followed by some activity with members of host family (typically, sport, shopping, or helping with chores) or free time.

Saturday night: After dinner with host family, pub or café visit with similar-aged host sibling or other exchange students.

Sunday morning: Sleep in, followed by an hour of chatting to parents at home (after getting host family’s permission)

Sunday afternoon: Free time, usually a bike ride or run for me if weather permitted.

Further research

The information above is taken from my own experience and the experience of people I’ve spoken to, including former exchange students and former host families.

I urge you to seek additional information from people at your school or living in your area who have previously been foreign exchange students. Ask them how they spent most of their time, and how they found that life as an exchange student differed from life in your home country.

Decision time

Once you have as complete a picture in your mind as possible of what a foreign exchange student does, ask yourself this question:

Given my personality, my goals in life, my work ethic and my personal strengths and weaknesses, and given what I now know about the life of an exchange student, am I prepared to live that life for six or twelve months?

It’s a very tough question. Make sure you answer it as slowly as you need to, and as honestly as you can.

Good luck,

Matt